Social Media: What’s Not to Like?

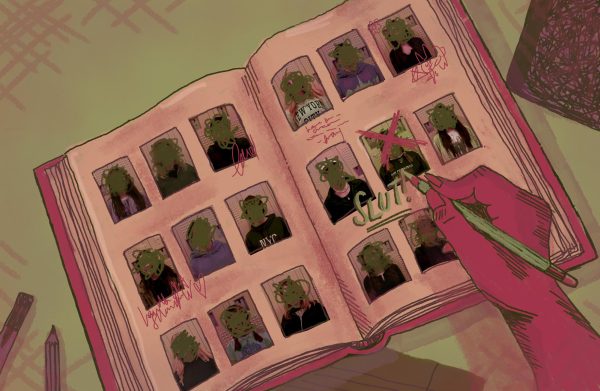

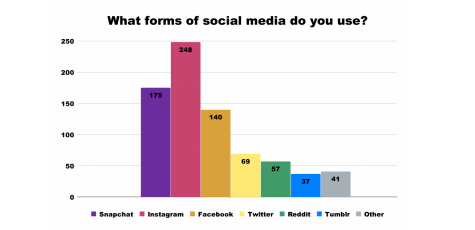

Scrolling through the Lowell Confessions page on Facebook, one can find these messages along with over 7,700 other anonymous posts. Similar sentiments of Lowellites’ mental health struggles can be found speckling Instagram feeds and Snapchat stories, as students turn to social media to vent and escape from school stress. With a survey conducted by The Lowell revealing that our students are 5.9 percent more likely to experience anxiety or depression than the national rate and that 98 percent of our student body uses social media on a regular basis, it is of little surprise that the issues of mental health and social media often intersect. Given this growing trend, it is important to question when social media use crosses the line from a successful coping mechanism to an aggravation of mental health issues.

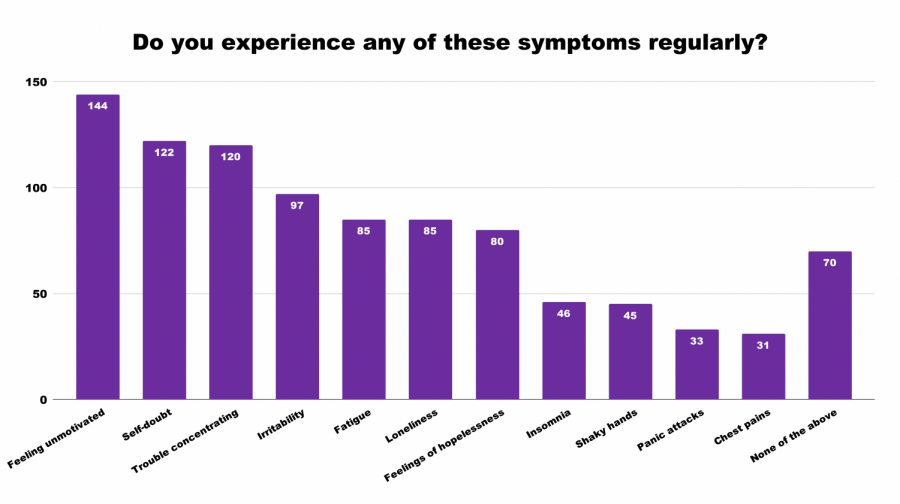

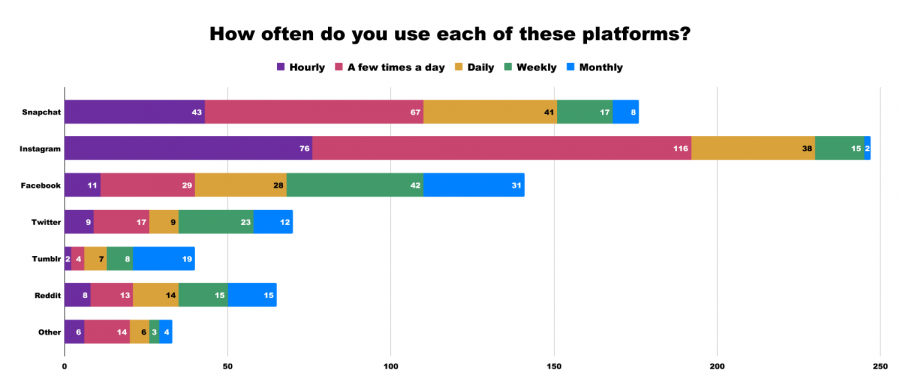

Since freshman year, Jane, a junior who has opted to use a pseudonym, has noticed her mental health on a steep decline. Upon arriving at Lowell, she struggled to adjust to the long school days, heavy course loads and competitive atmosphere, and soon found herself “crying more often” and stressing over her dropping grades. Faced with symptoms such as hopelessness, loneliness and feeling unmotivated, Jane began searching for methods of escaping her growing anxiety and depression. “Ever since I got into high school, I wanted to avoid work more often,” she said. “So I often went on social media.” To Jane, “often” has come to mean using Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, and Facebook all on a regular basis— Instagram every waking hour.

However, Jane has found that scrolling through endless posts from fellow Lowellites and K-Pop fan accounts have not helped improve her mental health, and in fact, it has compounded the issue. “I see people post they’re on vacation or they’re doing successful stuff, and I kind of feel like I’m not doing anything with my life,” she said. This sense of missing out and jealousy has, over time, eaten away at Jane’s self-esteem, as well as her free time. “I spent more time on social media,” she explained. “And that got in the way of work and sleep.” Jane sleeps on average 4 to 5 hours per school night, only half of the 8 to 10 hours recommended to teens by the National Sleep Foundation. This deficit has fed into a vicious cycle. Anxiety and depression lead her to check her favorite apps, she becomes absorbed in the constant flow of content, her sleep is compromised, she performs worse at school, and her mental health issues are exacerbated. Jane is currently attempting to break this toxic loop through meetings with a Wellness Center counselor from whom she learns about healthier social media habits, like not comparing herself to others online, but she’s yet to experience results.

Our students are 5.9 percent more likely to experience anxiety or depression than the national rate.

According to junior Stella McGinn, president of Lowell’s Mental Health Awareness club, many Lowellites are falling into similar cycles with their mental health due to social media’s influence, though they might not realize it. “[Students] have been clouded by, ‘I have so much anxiety, I’m suffering from panic attacks, everyone does. It’s Lowell,’” she explained. “But I think something that’s been weaved into our minds so slyly is social media usage.” McGinn considers the root of Lowell’s primary mental health crisis to be our school’s “strong culture of suffering,” in which students become immersed in a twisted competition over who has the hardest schedule, the most homework, and the least sleep. Overloaded with this stress, she feels students are turning to social media as an all too accessible form of relaxation and escape from their workloads, despite the fact it can make matters worse. “I think social media has had a very negative effect on our collective generation,” she said. “This is the first time that students and teenagers have cell phones [with which] they can contact virtually anyone in the world via social media; there’s a strong idea of fear of missing out.”

Though McGinn acknowledges this accessibility can connect like-minded individuals and provide harmless entertainment, she feels the constant flow of updates on other people’s lives can be harmful due to the “mask” many constructs for themselves online. “People don’t portray who they actually are,” she explained. “Just what society wants them to be, what looks best.” McGinn has found this issue particularly prevalent within the growing Instagram modeling industry. She has observed how seeing heavily edited images of models on Instagram’s Explore page can cause students to question, “Why don’t I have skinny thighs? Why don’t I have a waist that small? Why doesn’t my skin look as clear as theirs?” This negatively affects their body image.

Ever since I got into high school, I wanted to avoid work more often. So I often went on social media.

The concept of Photoshopped models influencing how teenagers view their bodies has been robustly supported by research from the National Eating Disorder Association, which found “exposure to and pressure exerted by media increases body dissatisfaction and disordered eating.” However, McGinn feels that the issue is worsening due to social networking sites. In comparison to magazines where runway-ready bodies are the expectation, teens are bombarded with more unrealistic beauty standards than ever before on sites intended for capturing real- life moments. “[These images are] so extremely accessible,” she said. “And it’s dangerous because the earlier someone gets their phone, the more likely they are to go down that rabbit hole and potentially get eating disorders and mental health issues.” This trend of users inaccurately representing themselves online is a major contributor to the depression and feelings of inadequacy many students like Jane are left with after turning to social media for comfort.

Megan Alvarado, the program coordinator of the National Alliance of Mental Illness’s San Francisco branch, also recognizes the dangers of Lowellites turning to social media to cope with school-related anxiety and depression. Having personally lived with depression since her teenage years, Alvarado understands the appeal of retreating into the internet; however, she has found such online activity devoid of the emotional connections necessary to truly help those struggling with their mental health. “There is a growing body of research that is looking at the connection between social media and mental health, and one of the things that’s being most talked about is how social media is actually linked to feeling isolated and feeling lonely,” she said. One particularly relevant example Alvarado cites is a 2018 study conducted at University of Pittsburgh. The researchers concluded that negative online experiences have higher potency than positive experiences, and individuals already expressing symptoms of depression might be inclined towards more negative interactions on social media. These findings perhaps explain why Lowellites like Jane tend to experience negative effects when turning to social media in depressed and anxious states.

DATA FROM A RANDOM SURVEY OF 300 STUDENTS

(3 REGISTRIES PER GRADE) CONDUCTED BY THE LOWELL IN

JANUARY 2019

Despite these findings and the experiences of students such as Jane, The Lowell’s survey revealed approximately 46 percent of Lowell students don’t feel there is a correlation between their symptoms of poor mental health and their frequent social media use. For example, freshman Leena Barqawi vouchers for social media’s value in sparking friendships and launching careers. Like the majority of her fellow Lowellites, Barqawi’s platforms of choice are Instagram and Snapchat, the former being her favorite. Between scrolling through the site’s vast array of content and keeping in touch with friends, Barqawi spends two hours a day on Instagram (not including the minimum hour she spends every two weeks taking her photos for posting). Her interest in Instagram was initially piqued in 6th grade upon seeing her older sister using the app, and Barqawi has subsequently racked up nearly 2,800 followers. Barqawi credits her large following in helping her acclimate to Lowell. She found it made making new friends easier. For example, before even arriving, older students began sending her direct messages with school advice. She also considers the maintenance and growth of her social media presence an investment for her future. Hoping to follow in family members’ footprints, she is planning on pursuing a career as a fashion influencer, and knows having a large platform to showcase her clothing tastes will be worthwhile in the industry.

Barqawi feels her experiences with social media and mental health have overall been more positive than negative, yet she recognizes the issue is not entirely black and white. She has received the occasional hate comment on her pictures, at times compares herself to other girls “living lux lives,” and feels the need to keep her photos looking flawless and “better online than in person.” That being said, she does not believe her social media usage plays a role in aggravating school related anxiety. “I can’t say much because I’m still a freshman, but so far school hasn’t completely ruined me,” she said. Lacking significant school-related stress to begin with, her Instagram has remained simply a tool for creating an idealized image of herself to share with friends and grow a following.

DATA FROM A RANDOM SURVEY OF 300 STUDENTS (3 REGISTRIES PER GRADE)

CONDUCTED BY THE LOWELL IN JANUARY 2019

Additionally, some students have discovered social media as a useful platform to vent about their mental-health issues, and thus help themselves cope. A senior co-administrator of the aforementioned Lowell Confessions group on Facebook (who has decided to remain anonymous due to the nature of the page) agrees with this point of view. He too has observed what McGinn dubbed as Lowell’s “culture of suffering” and believes it creates an environment in which students only feel comfortable sharing their struggles with mental health through an anonymous, digital interface. He says many submissions are prefaced by such comments as, “I didn’t want to say this myself because I know the people around me will just be like ‘Oh no you get more sleep than me you can’t be stressed’,” which he finds problematic. “The mental health of the school isn’t in the best shape,” he added. “The most common submissions we get are someone…stressed about some course, or they’re stressed in general.” Given this primary trend of anxious and depressive statements in the submissions (which according to the page’s co-administrator were sent in at a rate of seven to ten per day last year), he thinks Lowell Confessions has been a good outlet for Lowellites over the past six years. “I think any nonviolent expression is good,” he said. “It is helpful to get [their emotions] out so they don’t feel as alone.” To Jane, who has read Lowell Confessions posts in the past, seeing people finally expressing similar emotions helps her feel slightly less isolated. Instead of feeling alone, she can commiserate with her peers.

Barqawi and the Lowell Confessions page bring up valid points about the positives of our student body’s social media usage, but the fact remains that according to The Lowell’s survey, 30 percent of Lowellites feel social media has directly contributed to them experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression, the most common of these including feeling unmotivated and having self doubt. So how can students avoid aggravating school-induced mental health issues through social media use?

DATA FROM A RANDOM SURVEY OF 300 STUDENTS (3 REGISTRIES PER GRADE)

CONDUCTED BY THE LOWELL IN JANUARY 2019

One solution is going on social media cleanses. Senior Sheena Leong has purged her life of all social networking sites four times during high school, and she feels these cleanses have tremendously improved both her self-esteem and productivity. Prior to embarking on any cleanses, Leong says she spent a lot of time each day using Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook. “It really did debilitate my self image,” she said. “When everybody is posting these Facetuned pictures, it’s kind of like you’re inclined to conform.” In addition, she often turned to Instagram to rant about stress at school on her spam account — an account followed only by closer friends — which she didn’t consider a successful coping mechanism. During junior year, inspired by her mother’s frequent remarks to “put down your phone,” Leong decided to try and log off her apps for at least a month. Her longest cleanse ended up lasting nearly three months, and she began feeling the positive effects of “focusing more on [her]self.” Not only did Leong start sleeping eight to nine hours per night and feeling her productivity skyrocket, her self-esteem also drastically improved. “I used to wear a lot of makeup because of social media’s influence,” she said. “But once you get off [the platforms] you kind of realise you don’t need it.”

Though her cleanses eventually ended due to the need to communicate with visitors from out of town, Leong plans on returning to social media cleanses during college and highly recommends them to fellow Lowellites. “I found that being on social media took away time from being academically focused,” she explained. In college Leong wants to be laser-focused on her school work, so she thinks these periods of abstaining from social media will prove beneficial. Leong also feels that if more Lowell students went on social media cleanses, our student body’s overall mental health would improve. “A lot of people complain about stress, but I don’t think it’s just the academic factor… I think social media is a big part [of it],” she said.

For many Lowell students, this method of just shutting down their online presence is difficult due to the addictive nature of social media. Jane has attempted her fair share of social media cleanses, but always “felt the urge to download the [apps] again.” Alvarado suggests that instead of completely halting social media usage, Lowellites should instead just be more conscious of how much time they spend online and how they feel while using social networking sites. “One of the things that I’ve started doing for myself is really checking in with myself on how I’m doing while I’m using the app,” she explained. “So if I’m not really having a good time, I don’t need to be using it then.” She believes monitoring these factors will force students to step back and reevaluate their usage before it becomes detrimental.

McGinn alternatively feels that the solution to the toxic loop of mental health and social media at Lowell is providing students with healthier coping mechanisms altogether. She recommends journalling over venting emotions into spam accounts and pages like Lowell Confessions. She believes online posts about anxiety and depression might put the negative ideas into other Lowellites’ minds and feed into the campus’ culture of suffering, whereas individual self-care is more effective. The Wellness Center with its wealth of resources, therapy programs like 7 Cups of Tea, and simply talking openly in person with close friends or a trusted staff member are also methods she endorses. “Just make sure you have time for yourself, separate from your schoolwork or your phone, and make sure you do something you enjoy,” she said.

Traditionally, the factors contributing to Lowell’s high rates of anxiety and depression have been identified as our academic rigor and competitive culture, but the influence of social media has often been overlooked. “School leads to stress, then stress leads to ‘Hey I need to take a break!’ and then you go on social media because it’s right there,” McGinn said. “That leads to more stress and anxiety, you don’t do your homework, it’s a cycle.” In order to break out of this pattern, both she and Alvarado believe students must step back and reconsider their social media usage and how it actually affects their lives.