A new way to cheat

ChatGPT can write essays for students. What happens now?

Looking at the clock, it’s half an hour until the paper is due. Timothy, a sophomore under a pseudonym, sweats profusely as the deadline approaches. Staring at the blank screen, his stomach ties into a knot; in addition to the stress of being a slow typer pressed for time, the topic is complicated and requires deep planning that he no longer has time for. Remembering a conversation with his friends about a software program called ChatGPT, Timothy logs in and asks the chatbot to write him an essay on the topic. Watching the essay form on his screen, he wonders why he didn’t do this sooner. Having a finished product in a matter of seconds, the tension releases from his body.

Timothy is not the only student at Lowell who has used artificial intelligence writing software to complete schoolwork.

The rise in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to write essays has concerned teachers across the country. Certain AI programs are able to generate answers to any question or prompt that users input, leading to some cases of students attempting to use it for completing writing assignments. However, it has arrived at Lowell with mixed feedback. Some students use it due to family pressure, stress, or as a useful learning tool, while others do not see it as necessary or are directly against its use.

Differentiating between a human writer and AI is becoming more difficult, raising concerns about undetected academic dishonesty. The release of ChatGPT this past fall was a turning point. The ease and speed with which a ChatGPT user can generate writing blows minds, as does the quality of the text. Within seconds, it is able to write an essay, complete with a thesis statement and such teacher-pleasing qualities as varied sentence structure and analysis that ties back to the original claim. According to a research paper by the Stanford Center for Research on Foundation Models (Stanford CRFM), AI writing chatbots such as ChatGPT are trained through foundation models, a feedback system to refine responses generated from a vast quantity of documents it has access to. As a result, an AI chatbot can generate human-like writing.

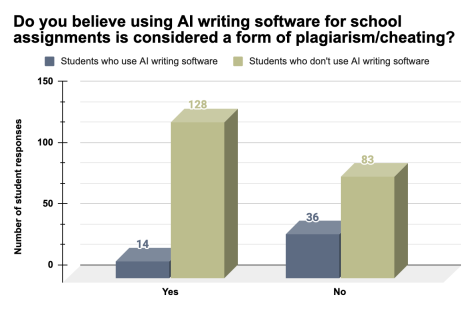

The use of AI writing software for assignments is against district rules. According to the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) Student and Family Handbook, “Any type of academic dishonesty, including but not limited to cheating, plagiarism, submitting work done by another as your own, or using unauthorized technology is prohibited.” Despite this rule being in place, Lowellites use AI for their written assignment. In a survey conducted by The Lowell, 19 percent of students reported using AI-powered writing software to complete classwork, essays, or tests.

Some educators at Lowell are less anxious about the plagiarism associated with AI and are instead worried about the loss of critical thinking skills. Social studies teacher Erin Hanlon-Young is one of them. “I’m asking them to write papers because I’m asking them to figure out what they’re interested in, how to find information, and how to make connections,” Hanlon-Young said. Lowell English teacher Jennifer Moffit also expressed worry over students having an easy way to avoid writing. “Writing is not just about having the correct answer; it’s also about developing that answer, developing your thoughts, through the process of writing,” she said. “Having AI write for them means that they will lose the opportunity to develop both writing and thinking skills.”

The main reason I used it was because my parents had put all this pressure on me to do better and to be a straight-A student. I couldn’t take it anymore and started cheating with ChatGPT.

Some students at Lowell are also apprehensive about the use of AI at school. “The whole point of getting an education is to learn and improve. And I almost feel like you’re doing yourself a disservice by using AI to get through that,” senior Ivy Mahncke said. The essays that high schoolers are writing emphasize the importance of drawing connections, and Mahncke feels like the loss of those critical thinking skills could leave students unprepared for the real world. “I am sure there are positive aspects to AI, but I think that the risk right now is so overwhelming that I almost wonder if the discussion is even worth it,” she said.

For some students, relying on ChatGPT is necessary to juggle what they consider to be overwhelming amounts of work. James, a senior under a pseudonym, resorted to ChatGPT for both school and scholarship essays due to time pressure. “Our society made it so that students have to take a lot of AP classes, have jobs, have clubs to be considered for admission in these really good colleges. Obviously, that can cause students to put a lot of work on their backs,” he said. “I feel like I can’t just be myself and be happy and be free, have time for myself because [of] all these assignments.”

For other students, ChatGPT has turned into an essential resource due to parental pressure. Timothy started using AI because all of his grades began dropping and he didn’t know how to maintain them. “The main reason I used it was because my parents had put all this pressure on me to do better and to be a straight-A student,” he said. “I couldn’t take it anymore and started cheating with ChatGPT.” Timothy’s mom would compare him to his brothers and other family members, and using ChatGPT for writing assignments offered a quick solution and allowed him to spend more time on other work to raise his grades. “She would say stuff like, ‘You embarrass me. Why can’t you be more like your cousins?’” As a solution, Timothy felt like he had no choice but to use text software.

Despite the apparent power of the writing programs, they have their flaws. ChatGPT, for example, struggles with subjects that require technical expertise or up-to-date knowledge. Senior Wallace Tang has attempted to use ChatGPT for class assignments such as poems or essays but found that it struggles to follow requests like writing in iambic pentameter or using up-to-date information, rendering ChatGPT’s answers unusable. In two articles from OpenAI, the publisher of ChatGPT detailed the limitations of the program: “ChatGPT’s training data cuts off in 2021. This means that it is completely unaware of current events, trends, or anything that happened after its training,” or even “ChatGPT will occasionally make up facts or ‘hallucinate’ outputs.”

Hanlon-Young sees the usefulness of ChatGPT in her classroom. After experimenting with the software herself, she found that it works best for her when generating essay questions. She had her class brainstorm topics related to U.S. history, then open ChatGPT and ask it to generate writing prompts for students to respond to in an argumentative essay. The program ended up helping some of her students find some direction for their interests. According to Hanlon-Young, when one of her students was struggling to think of how he was going to write about human experiences during the Great Depression, ChatGPT provided a prompt asking him to compare urban life versus rural life during the time period.

A major concern about using AI is the biases that stem from the algorithmic data that it is fed. Since language AI only has access to certain information, it forms a view that is informed by patterns it sees in that data. According to Stanford CRFM, “Foundation models can compound existing inequities by producing unfair outcomes, entrenching systems of power, and disproportionately distributing negative consequences of technology to those already marginalized.” It found that intrinsic biases that were present in the data fed to the programs surfaced in responses that it generated. This fact troubles Hanlon-Young: “What is this going to do to perpetuate systemic inequality, whether it be racism, sexism, xenophobia, classism?”

The biases ChatGPT reinforces also have the potential to work disinformation into the classroom. “It’s going to be a pretty major issue, especially when less technologically inclined people are using this more and more often, and they’re taking some of the stuff generated as fact, but it’s not,” Mahncke said. “There’s almost too much trust in the reliability of the AI and what people really have to realize is that it makes stuff up and it picks up biases from its sources.”

The whole point of getting an education is to learn and improve. And I almost feel like you’re doing yourself a disservice by using AI to get through that.

— Ivy Mahncke

The use of text-based AI for school remains controversial. The writing skills of AI will continue to improve, to the point where it may become indistinguishable from human writers. Since it could be used directly to cheat, questions of ethics and how to regulate it are brought up, as well as how it will impact the students using it. “I think it is like drug addiction,” Mahncke said. “It’s a little bit like pressing the dopamine button and like getting content for free and so I worry a bit what it’s doing for our own motivation to create, as opposed to just getting endless streams of content.”

Marshall Muscat is a Senior at Lowell. When he isn't busy taking a history class meant for juniors, he is biking, listening to sad music, or trying to explain physics to people that aren't interested in it.

Alina, a chocolate-averse junior, has an impressive list of never-tried foods, from boba to salad. She perpetually yearns for her sophomore AP biology class and can be found indulging in Chinese calligraphy painting and guqin playing. Yet, more often than not, she happily embraces her cozy potato persona, radiating warmth (or maybe exhaustion) wherever she goes.