Addressing antisemitism

As antisemitism rises across the nation, some Jewish students find themselves on the receiving end of hatred — at school and online.

Senior Sophia Paris rushes down the hallway, flustered as she heads to her next class. From the blurred body of students maneuvering to get to their classrooms, something is yelled out at her. Taken aback, Paris freezes before turning to look. In disbelief, she realizes she has just been called an antisemitic slur. Paris’s feet suddenly feel stuck to the ground as shock rings out in her ears.

Incidents like these are not isolated among the Lowell community.

Antisemitism — prejudice or hate directed at Jewish people — has been an issue for centuries. Yet in the past few years, a visible rise in antisemitism has been making its way through the United States, with antisemitic comments made by high-profile figures and conflict overseas influencing how Jewish people are treated and perceived. At Lowell, these influences often take the form of antisemitic comments or microaggressions on campus and online, leaving many Jewish students feeling scared and isolated. As a result, some students are turning to the Jewish community for support. Others believe combating the spread of antisemitism calls for action on behalf of the school, specifically in expanding curriculum surrounding topics such as the Holocaust.

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) received 2,717 reports of assault, harassment, and vandalism targeted at Jewish people in 2021, an all-time high in the United States. This was a 34 percent increase from 2020. According to the ADL, the coming years are expected to follow this trend.

This rise in antisemitic incidents is directly linked to the visible antisemitism displayed by politicians and high-profile figures, as stated by Dov Waxman, professor and Chair of Israel Studies at UCLA, in an interview with PBS NewsHour’s John Yang. Throughout 2022, rapper and designer Ye — formerly known as Kanye West — used his Twitter platform to praise the Nazi party and amplify antisemitic stereotypes and conspiracy theories. Prior to his account’s suspension, Ye had over 31 million Twitter followers, more than double the global Jewish population. In November 2022, former president Donald Trump dined with Ye, as well as Holocaust-denier and white nationalist Nick Fuentes, at his Mar-a-Lago club in Florida. Other politicians have added to this pattern of antisemitism, with U.S. Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene comparing COVID-19 related vaccine and mask mandates to the treatment of Jewish people during the Holocaust. Although public displays of antisemitism are not new, these incidents have allowed antisemitism to become increasingly acceptable in public discourse, according to Professor Waxman.

Modern-day antisemitism has also been shaped by the current problems in the Middle East. As reported by the ADL, the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict has increased anti-Israel sentiment. Because of the close association between Israel and Judaism, many have automatically associated pro-Israel figures with the entire Jewish community, leading to a subsequent rise in anti-Jewish tropes.

At Lowell, antisemitic incidents are not a new occurrence. In January 2021, anonymous users posted antisemitic and racist slurs, pornographic images, and other derogatory comments to an online Padlet discussion forum, sparking public backlash. Yet for many Jewish students, their exposure to antisemitism has been more visibly heightened by the events of the past year. Compared to the Padlet incident, senior Lexi Klionsky believes external factors, including Ye’s actions and the conflict in Israel, are having a greater influence on how Jewish people are treated on the Lowell campus.

For some students, the most visible antisemitism at Lowell comes in the form of microaggressions. As

described in professor Derald Wing Sue’s book Microaggressions in Everyday Life, microaggressions — slights, insults, and other offensive behaviors directed at people of marginalized groups — are often reflections of implicit bias, not intentional acts of discrimination. In turn, Jewish students are faced with coded language and imagery that others may not know is antisemitic. “I’ve definitely gotten offhanded comments [about being Jewish] at Lowell and it’s not out of a place of aggression, but because people aren’t educated,” Paris said.

Fear of facing antisemitism at school has prevented some students from expressing their Jewish culture. Senior Julian Rapaport feels apprehensive about wearing a yarmulke — a headcover commonly worn by Jewish men — at school due to concerns about antisemitic microaggressions. “I have not worn a yarmulke in school… and I probably wouldn’t,” Rapaport said. “Because on Saturdays, when I walk to synagogue, that’s when I get little comments that I don’t want to get at school. Forget it.”

For other students, social media has fueled their increased exposure to antisemitism. Junior Dahlia Kelly continues to see antisemitic posts uploaded to TikTok and Instagram, despite these media outlets committing to a crackdown on hate speech. “It’s not rare to be scrolling down and then see somebody say something antisemitic, or repost something Kanye said,” Kelly said. They also believe that this influx in antisemitic content is having an influence on students’ behaviors. “We’re all impressionable teenagers, and we see [antisemitic] stuff on social media which we absorb — consciously or subconsciously,” Kelly said. “So our behaviors become reflective of these posts or tweets or videos, and then there’s more chance for antisemitism.”

“I think part of [the issue] is that we want recognition for existing, and that just doesn’t happen.

In particular, Ye’s social media comments have sparked conversation among Lowellites. Paris has heard her classmates laughing about Ye’s antisemitic comments, and others defending him. “I heard someone say, ‘Yeah, but he wrote this good song.’ And I was like, ‘Shut the f*ck up right now,’” Paris said. Klionsky agrees that Ye’s large influence is extremely detrimental, and was scared for herself and Lowell’s Jewish community after seeing these comments.

Many Lowellites feel that the issue is minimized by both students and the administration. Some Jewish students feel that they aren’t recognized as a minority group at Lowell, causing their reports of discrimination to be invalidated. “I think part of [the issue] is that we want recognition for existing, and that just doesn’t happen,” Paris said. A similar sentiment was shared by Jewish students after the Padlet incident, with many students feeling that the antisemitic language cast against them was ignored by the administration. “I never officially saw the Padlet but I heard there was a ton of antisemitic stuff that was completely brushed to the side,” Paris added. “Nobody brought it up.”

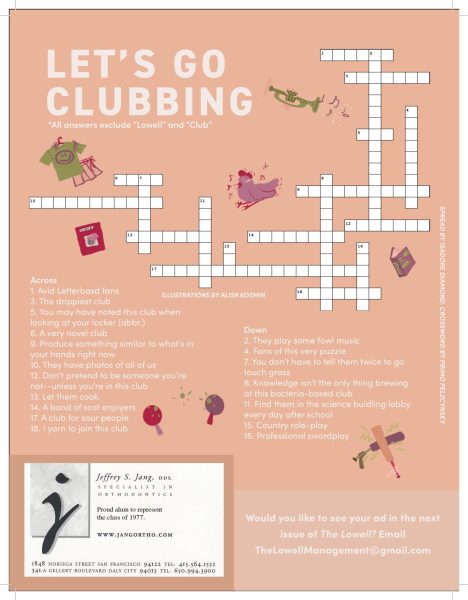

Some Jewish students have turned to communities including Jew Crew — Lowell’s Jewish club — to find support amidst these acts of antisemitism. “[Jew Crew] is a place where a bunch of kids who may have gone through the same experiences can feel safe,” Klionsky, co-president of Jew Crew, said. “We want to encourage people to come to us if they are a victim of antisemitism.”

To combat this issue, some students believe that they should be educating themselves about antisemitism and the Holocaust. Klionsky said that a lot of microaggressions or comments made about Jewish people come from a lack of understanding. As a result, she believes a solution is for people to educate themselves. “If you’re not sure if what you’re saying is rude to Jews, or the Jewish community, look into it. It probably is,” Klionsky said. “I think in general, everyone needs to be careful with what they say, how they phrase things.”

“[Jew Crew] is a place where a bunch of kids who may have gone through the same experiences can feel safe.

Some students believe self-education is not enough. Rapaport believes that learning about antisemitism and the Holocaust without structured guidance can lead to further confusion and misconceptions. “When you research [the Holocaust] and when you just skim Wikipedia articles, it’s just the scope of it. It’s almost impossible to understand,” Rapaport said. “And that can lead to well, ‘Was it really that bad?’”

For that reason, some students think required education is needed to combat the spread of antisemitism. Specifically in regard to the Holocaust, Paris feels that the current history curriculum lacks the depth and nuance the subject warrants. “Millions of people were killed and that includes people who weren’t Jewish,” she said. “That has to be acknowledged.”

Other students believe that Lowell’s curriculum could expand to cover more than just the Holocaust. Klionsky wishes that the enduring conflict in Israel and Palestine could be taught so that students can better understand antisemitism and Zionism — the movement for the establishment and protection of a Jewish state. Kilonsky believes that having a safe-space to explore these controversial topics in school would be more productive than uneducated discourse outside of the classroom.

Although efforts are being made to improve California’s standardized curriculum surrounding topics such as these, many teachers still find themselves utilizing outside material in their lessons. In October 2021, Governor Gavin Newsom launched the Governor’s Council on Holocaust and Genocide Education, tasked with identifying resources to teach students about the Holocaust and other acts of genocide. However, according to History Department Chair Rebecca Johnson, much of the education students receive surrounding the

Holocaust is provided through supplemental material, rather than being standardized by the school or the state. “[The curriculum] is regulated in that teachers should teach about the Holocaust, but not in how they go about that,” Johnson said. Similarly, Lowell’s English Department does not have a selection of required books or lessons that incorporate material surrounding the Holocaust or antisemitism, according to English Department Co-chair Staci Carney. Some teachers at Lowell choose to teach books such as The Chosen or Maus, which have led to discussions in the classroom about World War II, antisemitism, and the Holocaust. Some students feel very fortunate to learn about these topics through literature. “I was very lucky to have read Maus in class,” Paris said. “I think it was pretty great and it brought up a lot of things that aren’t talked about, like the ghettos and the things leading up to the Holocaust.”

Whether at Lowell or across the nation, acts of antisemitism are bringing about fear and stress for Jewish students. Experiences with microaggressions on campus and on social media have led to several being uncomfortable expressing their culture. Paris, like many others, hopes that Jewish students at Lowell will be more recognized for the struggles they face in light of these events. “I think being acknowledged is one of the biggest things,” she said. “I’d just like to be acknowledged.”

Kelcie is a senior at Lowell who can be found in the journ room working, drinking coffee, and listening to music. Her older brother once mentioned that there are only three guarantees in life: death, taxes, and Kelcie not waking up to her alarms. She also happens to have a paradoxical relationship with chicken… go figure.

Tatum is a senior at Lowell. Outside of journalism, she can be found browsing the bookstore, struggling through her calculus homework, or listening to a seemingly unhealthy amount of Taylor Swift.

Danica is currently a senior. She enjoys reading, making art, and walking her dogs, and she will try any food once. She eats at least one fruit a day and has a disturbed circadian rhythm.

Charon is an illustrator in their senior year. They are non-binary and use they/them pronouns. Usually just a homebody with a love of the post-apocalypse and wild west genres. As well as an eye for collecting charms, pins, patches, and other knick-knacks. Currently hemiplegic and recovering from a stroke.

Kylie is currently a senior at Lowell. When they aren't in the Journ Room, you can find them enjoying a nice medium cup of an espresso chai latte with light ice and short pull, or watching terrible movies.