Gun violence hits home: How gun violence is affecting the Lowell community

Following the Parkland shooting, students at Lowell protested for better gun control. With their gaze focused on national issues, they asked, “Hey NRA, how many kids did you kill today?” They asked, “Is Lowell prepared for a school shooting?” But a question not frequently asked was, how does gun violence affect Lowell students?

Lowell breeds academic excellence in its students. The high school, in its quiet, inner sunset neighborhood, is free from the terror of gangs. Lowell students don’t own guns, nor do they face the repercussions of gun violence in their day-to-day lives. Lowell students are safe.

Right?

Wrong.

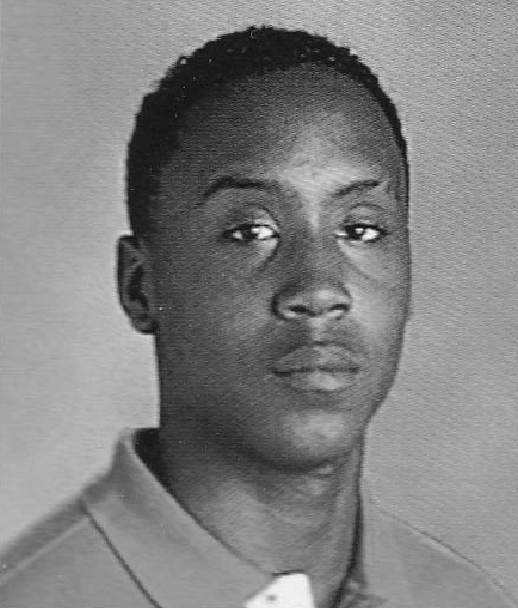

DARIUS THOMAS

On April 20, Darius Thomas was shot and killed down the street from his house. Thomas was a 20-year-old Lowell alumnus who graduated in 2015. He was hanging out with a group of five of his friends in San Francisco’s Bayview district when they were fired on by unknown persons in a car. Thomas was the only one killed.

Those close to him valued his sense of humor, and his sweet personality. He was passionate about sports, participating in Lowell football for two years, and was very involved in his church, the Bethel Cathedral Church of God in Christ, according to a statement released by Thomas’ family.

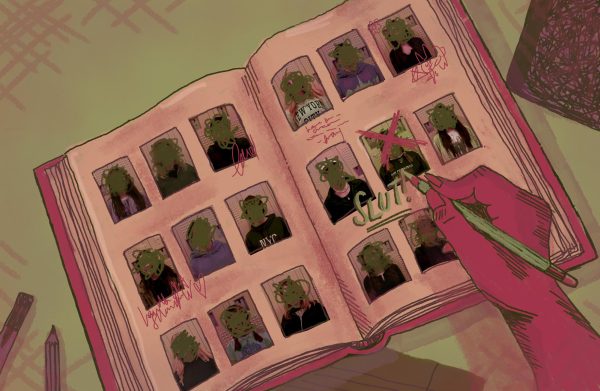

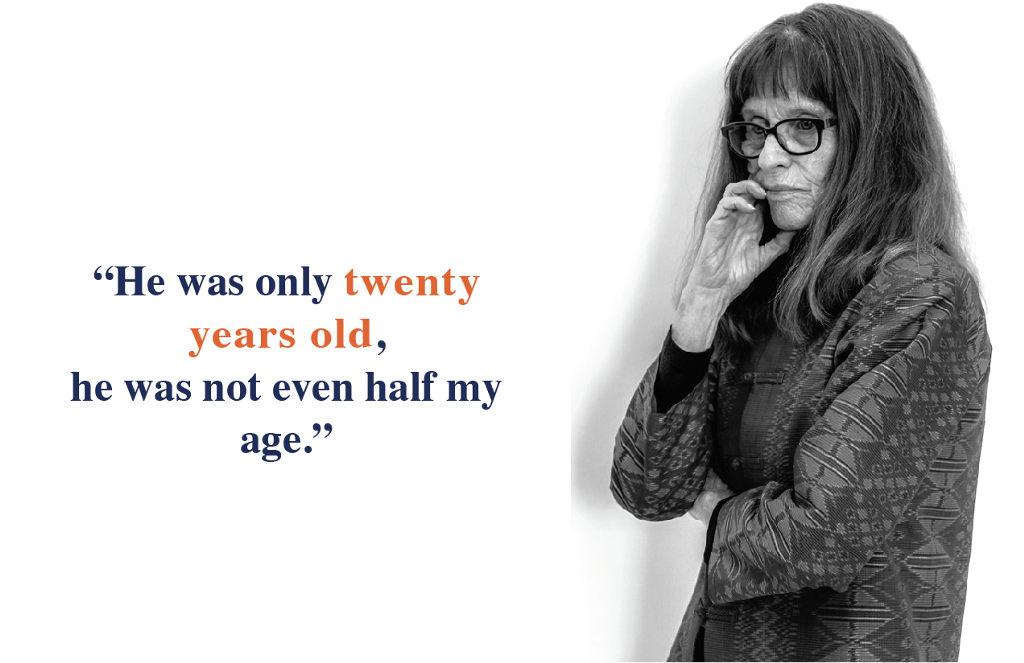

On April 23, three days later, Carolyn Nickels found out about Thomas’ death when a counselor asked to see a yearbook. He was looking for the photo of a Lowell alumnis who he had recently heard was shot. When he found Thomas’ photo, Nickels immediately recognized him as one of her former Registry students and was sickened. “He was only twenty years old,” she said. “He was not even half my age.”

Nickels remembers exactly where Thomas sat everyday for four years in her reg room — across her desk and a few seats over. “I watched him grow taller, and taller,” she said. “It was always really pronounced at the end of summer, when he’d come back to school he’d be a few inches taller or more.”

Nickels recalled one time when she choked on some food and asked Thomas for help. “Hit me, Darius,” Nickels said. Darius Thomas was twice her height. He stood up, and patted her gently on the back. Nickels, desperate, said, “No, Hit me, Hit me.” He patted her gently again. “It made me laugh so hard that he didn’t want to hurt me by really smacking me a good one, that the laughing caused the crumb to come flying out,” said Nickels. “And if it hadn’t been for him I might have died.”

Nickels sees a future in every one of her students, and never could imagine even one of them being killed. “When somebody is a real life, breathing, keeping-me-from-choking-to-death kind of person, you just think that they have got a life all ahead of them,” Nickels said. “Whatever it is, it’s all ahead of them, and they’re gonna make the world a better place. At least it’s what I tell my students.”

Thomas’ teacher Claire Puretz was also close to him during his time at Lowell. When Puretz found out through one of Thomas’ friends that he had died, an image of Thomas as a baby arose in her mind from when she was helping him choose one during senior year. “I’ll never forget that baby picture, how adorable he was,” Puretz said. “That just brought me back to the idea that regardless of if someone is invisible or visible in our minds, anyone who is a victim of gun violence was once somebody’s child, is loved.”

Puretz acknowledges that when young men of color are killed by gun violence, people are quick to draw conclusions about the activities that they were involved with. To Puretz, that’s not an important question. She believes that the most important thing is acknowledging who the deceased were and their lives as a whole. “For some people, when it’s gun violence and it’s a person of color, there are presumptions,” said Puretz. “And for me, I just saw him as a loving, caring young man, like many others who didn’t deserve this. But for many people the question is, ‘Is it gang related?’”

Puretz feels that it’s important to acknowledge the ways in which Thomas is and isn’t a statistic. She wants to raise awareness that a community member from Lowell has been lost and honor his life. But simultaneously, she feels that it’s important to acknowledge the way that he is similar to too many other young men of color: their deaths are due to gun violence. According to the the Everytown Organization, black men are 13 times more likely than white men to be shot and killed with a gun.

In San Francisco, from 2013–2017 there were 177 homicides by firearm according to the SFPD. Thomas’ death was the twelfth homicide of 2018. On average, 68 percent of homicide victims are killed by guns. This is similar to the California statistics for gun violence in 2016, where 70 percent were deaths due to firearms according to the FBI.

JOHN

The final straw was when John, a Lowell student who is using a fake name because he prefers to remain anonymous, got robbed at gunpoint. “The day after, I was like, ‘I’m not dealing with this, I’m not gonna be that kid who gets picked on,’” John said. The next day, John decided to buy a gun. It wasn’t very hard, after he reached out to a group of what he referred to as his “sketchy” friends. They showed him a wide range of guns, from small pistols to a large AK47 with a silencer on it and a design of a marijuana leaf carved into the wood. John went with the “cheap option,” a small pistol that cost $700.

John lives in a world that’s very different than his peers, though it is one of his own choosing; instead of worrying about his math tests he worries about getting robbed at gunpoint. John described his gun possession as “precautionary.” He has never shot his gun nor brought it to school, and he never intends to. John knows two other people at Lowell who own guns, and thinks that there are probably more.

“The day after, I was like, ‘I’m not dealing with this, I’m not gonna be that kid who gets picked on’”

John uses guns to make sure that he is treated more seriously during drug deals. “It’s not for pulling it out and pointing it at someone’s face, but mostly just to have it there so people know that you mean business,” John said. It’s also so that he can defend himself against people with similar weapons. In John’s case, because of the business he’s in, he thinks about guns and gun violence daily. “It’s definitely a factor that I have to think about when I’m going to meet certain people,” John said. “Do I have to be prepared? What’s gonna happen? When I’m meeting new people, I have to analyze: would this guy shoot me, could he shoot me?”

John was recently robbed again, this time by a pair of his friends during another drug deal. John went with a partner to a public parking lot to conduct a drug deal. He didn’t bring his gun because the buyers were his friends, and he didn’t expect any trouble. When John and his partner arrived, his two friends put a knife to John’s throat, and pulled a gun on his partner. After taking his duffel bag with the drugs, they ran away. John thinks that they were trying to get initiated into a gang by robbing them.

Most of the people John knows that have guns are involved with either gangs or serious drug dealing. According to him, the guns are a byproduct of the drug dealing and the gangs. He says that when you reach a certain point of seriousness in either, you need to buy a gun. “For the most part, a lot of the small time little peddlers will carry some sort of knife or something, but don’t need a gun,” John said. “But once you get into the whole gang violence aspect, then they get guns.”

Owning a gun has made John feel simultaneously safer and more at risk. With the lifestyle that he chooses, he feels he needs a gun to be safe. But having a gun means that he is participating in drug dealing on a higher level, putting him more at risk because he is in situations where he could have to potentially use it, according to John. “I would feel safer if I had a bulletproof vest and a gun, not just a gun,” John said. “It’s more like I hope I don’t have to use it.” He has considered that he could get shot, but chooses not to dwell on that, calling it “morbid.”

Although California gun control laws are some of the strictest in the nation, according to The Washington Post, it was easy for John to buy a gun. There are state laws about who can buy guns, ammunition and even what types of guns are legal. John thinks that his friends drove across state lines to purchase the guns in states like Nevada or Texas, which have looser gun control laws.

For John, it was harder to buy ammunition then it was to buy the actual gun. This may be in part due to California’s strict legislation surrounding the sale of ammunition. In 2018, new legislation was enacted that requires gun owners to buy ammo through licensed ammo distributors. Even if buying it online, they must buy it through a licensed distributor, and all purchases of ammo must be through a face-to-face interaction. Beginning in July of 2019, California will require residents to have a background check to buy ammunition.

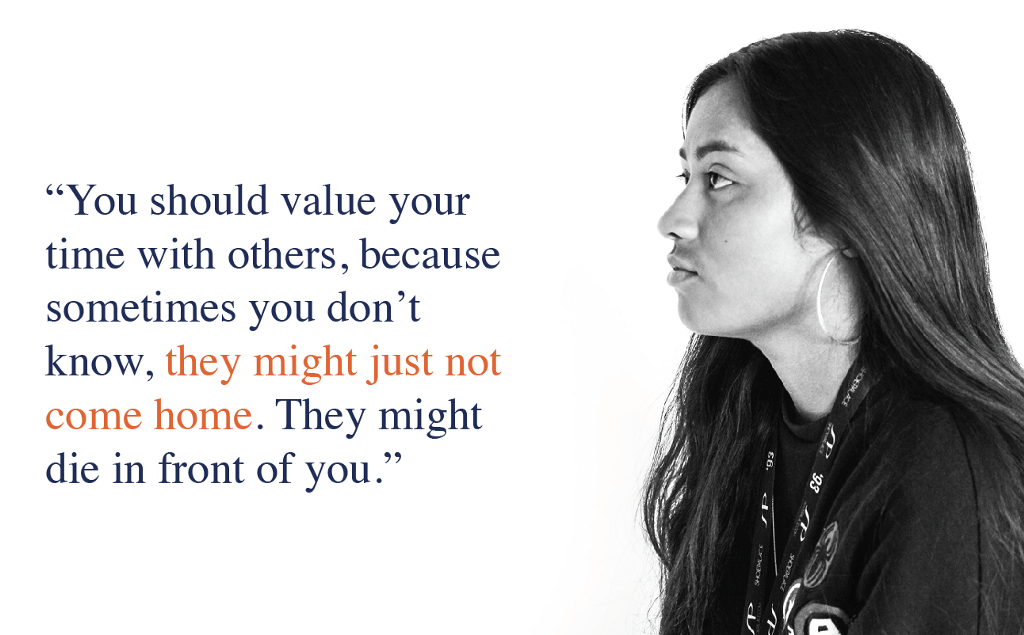

JOANNE FLORES

A line of police cars drove down junior Joanne Flores’ block and arrived at her house. Outside, the police rang the doorbell on her gate, and asked her entire family to go downstairs. The police officers stood in a line, their hats to their hearts. “We have terrible news to give you,” they said. “An officer has fallen and it was one of yours.”

Flores immediately knew that the officer was referring to her aunt. Flores’ grandmother screamed in pain, one hand to her heart, one in the air, exclaiming, “Please don’t tell me it’s true.” Flores and the rest of her family stood silently in shock.

In November 2017, Flores lost her aunt, 22-year-old Gisselle Glover, to gun violence. She had responded to an incident and gotten caught in the crossfire. Glover and Flores were very close due to their 5-year age difference. “She was the only person in my family that I could actually talk to,” Flores said. “She wasn’t like my mom or dad. It’s like I could talk about her as my best friend but get adult advice.”

Flores put a brave face on for her family and friends after Glover’s death, but she struggled with her loss. When she was alone she would lock herself in her room and think about how Glover died. “If she wasn’t in there at that moment, what could’ve happened, like could she still be here today?” said Flores. To Flores, Glover’s death felt unfair because she was only 22 and had a bright future.

Glover is not the first person that Flores has lost to gun violence. When she was nine, her family was living in Section 8 housing in San Francisco on Hill street. One day, Flores and her 11-year-old friend were riding down the street when shots were fired at him. He pushed her away so she survived, but he was shot and killed. Flores felt helpless after he died, there was nothing she could have done to save his life.

“If she wasn’t in there at that moment, what could’ve happened, like could she still be here today?”

Her friend wasn’t related by blood, but he treated her like a little sister. They grew up together and lived across the street from each other. “Losing him, it felt like I lost a part of me, because of the fact that he always looked out for me,” Flores said. “He always made sure that I was ok.” Five years ago, talking about his death would make her break down. But now, about 8 years later, it has gotten easier for her to talk about the incident.

Gun violence has not only changed those who surround Flores, but it has also changed who she is. Flores is more cautious and hesitant in opening up to people, a change from when she was a child. “As a kid growing up, I was more fun and open, but when I experienced my brother passing away, I felt alone,” Flores said. Because of the magnitude of her experiences with gun violence, Flores sometimes finds it difficult to relate to her peers who may or may not know how to handle what she’s been through or how to give her advice.

Flores views life differently because of her experiences with gun violence. Because she’s seen the way that people can so abruptly exit this world, she tries to value her time on Earth. It has especially shaped the way that she treats her family. “You should value your time with others, because sometimes you don’t know, they might just not come home,” said Flores. “They might die in front of you, you just never know.”

“As a kid growing up, I was more fun and open, but when I experienced my brother passing away, I felt alone”

Being a victim of gun violence makes Flores feel isolated from people inside and outside of Lowell. She thinks people view Lowell as “all rainbows and flowers,” an isolated place where students’ only concern is grades. “They’re quick to claim that we’re all just smart nerds and they don’t know anything about the real world and the struggle,” Flores said.

What sets Lowell apart from other schools is not only the record of academic excellence but the fact that its students’ problems lie hidden beneath the surface. Every day, thousands of students file through Lowell’s doors, some bringing their own experiences with guns and gun violence.

From teachers like Nickels who’ve lost students, to students like Flores who’ve lost family members to alumni like Thomas who’ve lost their lives, gun violence plays a very real and threatening role in the lives of people in the Lowell community, whether that role is apparent or not.