Sexpectations

Let’s talk about sex.

Often seen as the pinnacle of growing up in our culture, sex is a widely discussed milestone in students’ paths to adulthood. According to many Lowell students, before they experience sex, their expectations of it are formed by consuming media, hearing about their friends’ experiences, and societal norms spread on social media. Whether they are sexually active, not sexually active, or asexual, teenagers are struggling to reconcile their conceived expectations of sex while navigating the reality of their lived experiences. Students and experts alike agree that through education, inaccurate expectations of sex can be remedied and help students feel more represented.

Growing into one’s sexuality is a new, sometimes scary, sometimes exhilarating process.

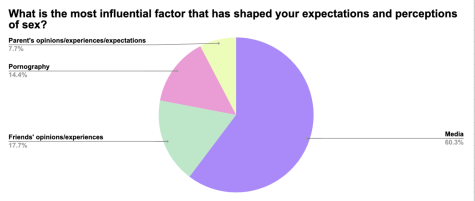

Consumption of media and spending time on social media plays a big role in shaping students’ expectations of sex. In an April 2022 survey conducted by The Lowell of 12 randomly selected registries, 60 percent of respondents said that media was the most influential factor in forming their expectations and perceptions of sex. Some students feel that many movies and TV shows set in high school hypersexualize teenagers’ lives, which influences their expectations of how much sex they should be having. “A lot of people do think that it’s a very big part of life, especially at this age, because all around you, you see sex being a very key part of the portrayal of high school experience,” Alex, a senior under a pseudonym, said. Lauren, a junior under a pseudonym, believes that students internalize the sexual experiences that they see on the screen as what sex is supposed to look and feel like. “A lot of people have this idea that it’s just like what they watch,” she said. “We are so young, we’re easily influenced by it.”

These expectations formed from the media and the Internet sometimes act as a type of informal education about sex, having the potential to shape how students move through their sex lives. Bob, a senior under a pseudonym, learned the majority of the information he knows about sex from the Internet. As a gay student, Bob did not see himself adequately educated about his sexuality in health class, which left him vulnerable to having his expectations formed from other, unregulated avenues. “There’s no curriculum…it’s just people telling you information, no matter how gross, no matter how bad, no matter how inappropriate,” he said. Informal education has consequences, according to experts. Ivy Chen, sex educator and gender and sexuality lecturer at San Francisco State University, believes that media portrayals of sex are inaccurate and harmful. “It sets up these super unrealistic expectations of how they’re supposed to act or what it means to be popular or to be accepted, what their bodies look like,” she said. “Unfortunately, I feel like it makes them feel like they have to be put in a little box.”

Social expectations are another factor that shapes students’ sexual literacy. When Lauren started dating her boyfriend, she felt like her friends who were also in relationships expected her to be having sex because of her relationship status. Although she is still a virgin, that social assumption makes her feel pressure to rush into intimacy with her partner. “There’s always this incentive for me to have sex or progress more into my sexual life even though I personally don’t want to,” Lauren said. “Just because everyone else is doing it, and I want to be included.”

There is also a cultural expectation of teenagers to lose their virginity that comes from being in high school. As students transition to adulthood, they experiment with and explore their identities, and sex can be an expected part of that. “You don’t want to enter the world without this experience, and high school is a natural place [to gain it],” Bob said. Some students also want to avoid being labelled as a “college virgin,” by starting college without having sexual experience. Maya, a senior under a pseudonym that has lost her virginity, made it a priority to gain sexual experience before she leaves for college. “I don’t want to go to college and be inexperienced and have no idea what I’m doing,” she said.

Losing virginity can be an affirmation of identity, especially for students in the gay community. Bob wants to have sex because he feels like it would validate his identity as a gay man. “The goal is sex, because [now that] you’ve discovered that you’re gay, you need to put it into action,” he said. “I do identify as a gay man. But if it comes down to it, like, I’ve never had sex, so it’s like do I know?” For Bob, having sex would be both a marker of growing up and settling into his sexuality.

Despite the possible expectations, and even pressure, for students to have sex, many are not. Eighty nine percent of survey respondents reported having had zero sexual partners, and 76 percent of currently sexually inactive people reported not wanting to be. Some students don’t feel adequately educated about the logistics and potential consequences of sex. Others are waiting for the right person to be intimate with. And the majority of Lowellities are not interested in it at this point in their lives.

Many Lowell students do not want to have sex. Sixty three percent of survey respondents cited not being interested in sex right now as the reason why they are not sexually active. Brendan, a junior using a psuedonym, doesn’t feel the desire or need to seek out sex right now. He has never dated someone or otherwise been in a situation where he would lose his virginity, and does not want to extend the effort to put himself into those situations. “It’s not something that I’ve really gone out of my way to pursue,” Brendan said. “I figure with school, friends — I have responsibilities already — that I don’t need to add more stress or just stuff on top of that.”

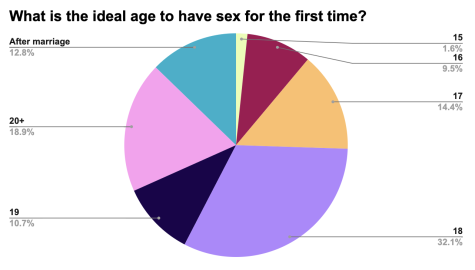

Students also cited wanting more time to mature before making the decision to be intimate with someone. Lauren thinks that she’s too emotionally and mentally immature to experience sex right now, and does not want to rush into something she may not be completely prepared for. “When you are still young, your brain isn’t fully mature,” she said. “Some ideas in the world we can’t really understand until we hit an age where we are like, ‘Oh, that’s what it means.’” Many students also link readiness for sex with maturity: 74 percent of survey respondents said that the “ideal age” to have sex for the first time was 18 years old or older.

Not knowing enough about the logistics of having sex can contribute to students’ wariness towards it. Despite taking health class before her junior year, Lauren doesn’t feel like she knows how to navigate all the potential consequences of being sexually active. “What if I get pregnant? What if something goes wrong in the middle?” she said. “What if I don’t feel good? What if I said yes but actually didn’t want it after?”

People who identify as asexual feel little or no sexual desire. That is the case for 10 percent of the students surveyed, and possibly for 17 percent who are unsure if they’re asexual or not. Alex acknowledges that for their peers, sex is a big part of the “teenage experience,” but that isn’t the case for them since they are asexual. “I feel much more comfortable not partaking in sex, just existing outside of those experiences,” they said. They feel confident in their asexuality, with the help of supportive friends. But this isn’t the case for all asexual people. According to Alex, some asexual people feel pressure to feign interest in sex because of other people’s judgments. They feel isolated for not feeling sexual attraction in a society that is hyper-sexual. “I heard, mostly online, from people in the asexual community that they felt like broken basically because they’re like, ‘I’m not interested in this’ and everyone else is saying, ‘Oh, you should be,’” they said.

Students that do have sex also find that it does not always match their preconceieved notions. Maya thought that she wouldn’t be physically satisfied during sex because she believed that male partners would not care enough about her pleasure, an idea she internalized from videos she saw on TikTok. Consuming videos from creators that painted a jaded view of sex with cisgender men caused Maya to expect that sex would be unccomunicative and unpleasurable. But when Maya had sex, she realized that her partner did care about her pleasure, and that it takes communication between both parties to truly develop a satisfying sex life.

When Maya first started having sex, her partner didn’t fully please her right away, but she didn’t voice her displeasure. Maya learned that she had to take initiative to speak up and tell her partner what felt good to her instead of stewing in the pessimistic mindset. “I felt like I was betraying myself, but once I spoke up, it was a lot better,” she said.

Realizing that it took open communication and a willingness to prioritize your partner’s pleasure contrasted the seamless, effortless portrayal of sex in media that Maya had previously consumed. “It’s very glamorous, they look great, it’s very easy…When a lot of the time, I think it’s not true,” she said. “It’s something you have to learn with your partner.”

There are also expectations that losing your virginity is a bigger deal than it is. Some students feel that dramatic, ceremonial portrayals of “the perfect first time” in various media can lead to heightened expectations. These expectations tainted senior Nikolai Hungate’s first time having sex, building up the suspense — and the pressure for it to be the perfect experience. “You always imagine your first time, right? You anticipate it, or at least I did,” he said. “Before I had sex, it was supposed to be a big deal in society.” Hungate’s first time was not flawless: he and his partner tried multiple times to have sex before it actually happened, once having to stop when he lost his erection due to nervousness. Hungate realized not only that having sex for the first time wasn’t seamless, but it also did not transform his identity. “When it happened, it was cool. It wasn’t like a life changing thing for me,” he said.

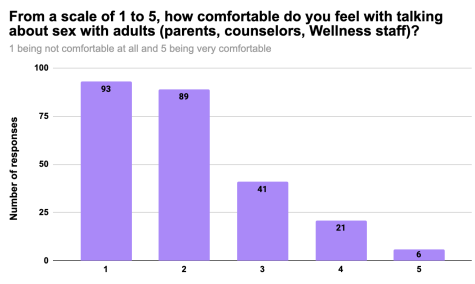

To bridge the gap between the different expectations and distorted perceptions of sex, students and experts alike think that education is essential. Chen, the SF State lecturer, believes that education is a valuable tool to help students feel comfortable in their sexuality and make informed choices about their sex lives. “The more knowledge that kids have about their own body and the more information they have about things like body autonomy and agency as well as consent, the safer they are,” she said. Lowell health teacher Judith Brooks agrees that sex education is an important tool for teenagers to make better decisions now and later on in life. Brooks expressed her concern with how late in their high school career some Lowellites receive sex education. Lowell is the only high school in the SFUSD district that allows students to take health class at any year, which leads to many students opting to take it in their seniors and juniors years. This leads to many not gaining helpful information before they need it. However, Principal Joe Dominguez has announced that all freshmen will be required to take Health, starting next school year.

You always imagine your first time, right? You anticipate it, or at least I did. — Nikolai Hungate

Chen believes education is the most effective when it is introduced early on, before students go through puberty. Because students are growing up in the digital age and forming their expectations of sex at younger ages than before, she wants formal sex education to happen earlier to counter this informal education. “When they do become teens or maybe start to experiment sexually or get into relationships, they already [will] have had years of this foundation of at least correct information and language to be able to talk about this even with their sex partners,” Chen said.

But the timing of sex education isn’t the only issue. The content can also be lacking. Many students feel like the current health class curriculum does not adequately go into depth on the topics they want to learn about. When Lauren took Health over the summer, the curriculum primarily focused on drugs and only scratched the surface of sexual health, spending one day on it and covering only basic knowledge, like the importance of using condoms. “It’s very bare minimum,” she said. “So that’s why I didn’t feel like I learned anything from it. I was kind of disappointed.”

Students want to see a sex education curriculum that reflects their actual questions about sex. Health class usually focuses on the biological aspects of sexual health, and some students want to learn about the emotional aspects of sex as well. Bob feels like Health didn’t teach him anything about the buildup to or aftermath of sex. “We don’t talk about liking people or any sort of emotional thing,” he said. “We just talk about [it] like, ‘This is sex. This is what happens. Don’t get an STD or pregnant!’ and that’s it.” Bob would like to learn about healthy communication habits around sex: how to tell if someone does or doesn’t want to have sex, and how to communicate those desires to partners. Bob also wishes concepts like aftercare, kinks and fetishes, power dynamics, and resources for queer students (like how to prevent HIV) were covered. Chen also wants to see a curriculum that is in tune with what teenagers want to learn about. “We have to look at the rest of that young person’s life to try to actually teach sex ed in a way that would feel like it makes sense for them to incorporate into the rest of their life, that it actually feels relevant,” she said.

This education that encompasses all aspects of sex, from the physical to the emotional, is important to students because they think it will help them develop healthier relationships. Alex emphasized the importance of educating students about consent in making sure that all parties feel safe and comfortable during sexual encounters, which is not always present in pieces of media. “A lot of guys who might not ask for consent, like they see in the media that it’s normal to not ask for consent to make those advancements,” they said. “And therefore, it’s just much more normalized to do things without asking for consent.” Bob believes that this education would help students identify when they feel uncomfortable during sex, potentially helping sexual assault survivors realize what happened to them faster. “If they taught stuff about when you’re being emotionally manipulated into having sex with someone, this would happen a lot quicker,” he said. Education about the emotional dimension of sex would also help students to truly focus on feeling good during sex, as opposed to the potential consequences of sex. “People forget that a lot of the time that sex is something you’re supposed to understand [and] grasp the concept [of], and then decide for yourself if you want to do it or not, and then enjoy it,” Bob said.

With the prevalence of the Internet only growing, Chen wants to adapt to the ways students are actually learning about sex. She believes that the future of sex education is online, and creating online learning tools to exist alongside entertainment about sex is essential. To do this, search engine algorithms could be reconfigured to bring up educational content about sex first, and cartoons geared towards younger kids could introduce sex in engaging and casual ways. “When we talk about sex and the way that it’s represented online, it’s often a bad thing…but I think that we could maybe use that tool for good, too,” Chen said.

Trying to remedy the distorted expectations that the media can create is another way that students may be able to feel more comfortable in their sex lives. Chen believes that as a society, we need to make a collective effort to remind ourselves that media portrayals of sex are unrealistic. “Anything that’s in movies or TV, it’s going to be an exaggeration of something because it’s meant to be entertaining,” she said. “It’s gonna sensationalize teens’ lives.”

Growing into one’s sexuality is a new, sometimes scary, sometimes exhilarating process. Hungate emphasizes the importance of remembering that sex is something that every teenager figures out for themselves, at their own pace. “It’s a new world you’re stepping into, and for some people it can be a pretty big deal, and so it can be scary,” he said. Maya wants students to know that they have control over how they approach sex. “Your consensual experience is really up to how you make it,” Maya said. “Don’t make your expectations too high, don’t think it’s going to be some fantasy thing.”

Marlena is a senior at Lowell. When she isn't at school she's probably at the lab, watching a movie, or sitting on the sidewalk listening to music (usually Björk).

Saw is a senior who has been on staff since Spring 2021. Outside of her busy academic life, Saw likes to volunteer at events, explore the city with friends, watch the latest MARVEL movie, and run on Lowell's Cross Country team.

Elise is a senior. This is her third year as an illustrator for the publication. Some of her interests include petting cats, going to museums, and spending unforgiving amounts of money on the evil coffee monopoly that some may know as Peet's.

You can usually find Dary blasting music in her airpods and speed walking around in outfits she spent too much time thinking about, or that embodies the Adam Sandler within her. She loves to chat, so feel free to say hi or ask for help!🍵