The Best Books are Banned Books

The first time I read Maus, I was not prepared for the vicious history of Nazi Germany depicted in the graphic novel. At the age of nine, Holocaust was just a term, and Nazis were grouped into the juveniley, simplistic category of “bad guys.” I stumbled across a copy in my grandmother’s house, drawn in by Art Spiegelman’s illustrations. I curled up, the springs of my grandmother’s spare bunk bed squeaking and my nose full of the musty smell of her antique perfume, and read it in one sitting. Rather than an entertaining story, I received a necessary one. And it changed my life.

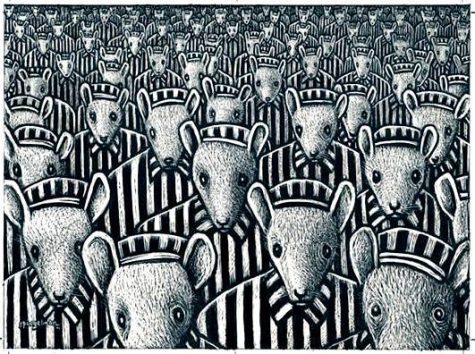

Maus scared me. The black and white drawings of Spiegelman’s story unfolded into a narrative of family, desperation, and the pain of the Jewish persecution in Nazi Germany. It was dark, showing the brutality of concentration camps and the gruesome reality of Nazism. It has also been one of the most formative novels I’ve ever read. And then, in early February of 2022, I realized this book was being banned in Tennessee because it was deemed too violent. I was shocked, momentarily teleported back into my grandmother’s home as I remembered the moral weight of Spiegelman’s memoir. I was worried, worried to lose a story that society needs to grow. Censorship limits our ability to understand and empathize with narratives that are not our own.

Books like Maus, and other banned works, can change people’s lives. They have changed mine, opening my mind to new perspectives and reshaping my morals. Every time a book is banned, we lie to ourselves about the realities of life. Censorship limits our ability to understand and empathize with narratives that are not our own. These “difficult” novels are necessary for social growth. They are not books to be banned — they are precisely the ones we should read.

I’ve read Maus multiple times since my initial encounter and I find myself returning to it again and again because of the humanity that shines through the story. Spiegelman’s memior chronicles his relationship with his father and his father’s survival of Nazi Europe as a Polish Jew. Maus takes the reader to the most intimate level of understanding around this bloody conflict and its ripple effect on future generations. It is the type of story that cannot be told by a historian or a Holocaust researcher as Spieglman is writing about his family’s experiences. Despite depicting one of the most horrific events in history, it doesn’t try to pass as pure historical analysis. The important aspects of Maus are the humanity and memories of Spiegelman’s father, not the sterilized facts of the past. You don’t get the personal connection of another human’s life in a history book, but you can see yourself in the pages of a story because you are also human. You can feel the emotions of the characters, feel his father’s desire to survive Auschwitz as well as the guilt he grapples with for having lived while so many did not.

It is this universal connection that arises from a narrative like Maus which makes it stay with you. And why it shouldn’t be banned. Whether it be in the smallest detail, like the use of a wooden coat hanger instead of a wire one, or the larger narratives of family dynamics, there are flashpoints for readers to connect. Banning Maus is a detriment to society because it tells a story we often aren’t able to hear: a tale of survivors from their own perspective. Authors like Spiegelman take the history we have and the narratives we know and twist them together like a pane of molten glass until the readers can see a new perspective on the same surface, side by side their own.

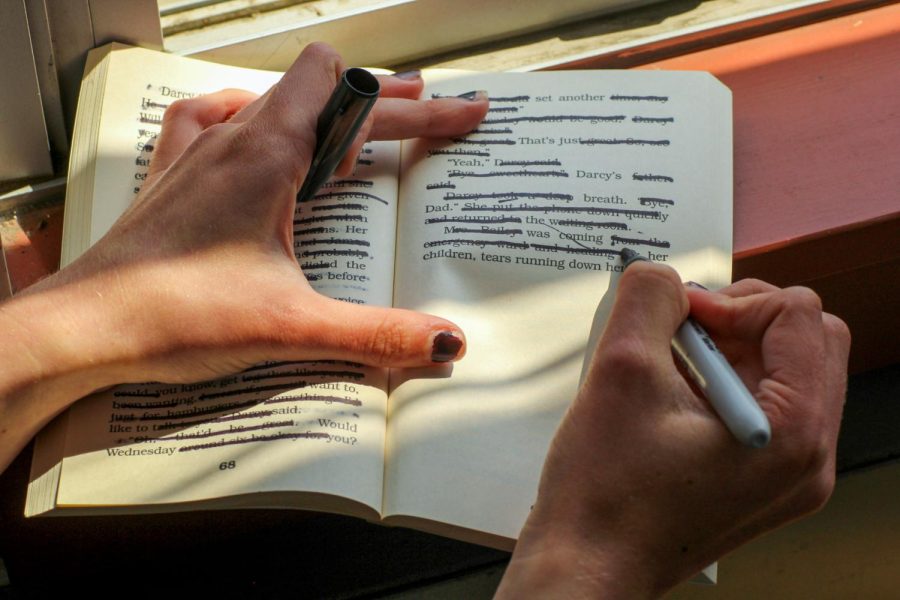

Many novels, memoirs, and non-fiction books have been branded as inappropriate for their discussions of race, gender, sexuality, or other obscene content, a label that ignores the larger, relevant criticism within the pages. However, these ideas — for books are truly just manifestations of ideas — are essential to our growth as a society. Books don’t always reflect our better angels, instead showcasing our darkest tendencies: war, rape, racism, slavery, and the brutal reminder that people are as vile as they are good. But these narratives spur discourse about progress, and banning books silences these necessary conversations before they even begin. These narratives spur discourse about progress, and banning books silences these necessary conversations before they even begin.

Even authors I abhor, such as Rudyard Kipling, who wrote horribly racist works including The Jungle Book and The White Man’s Burden, I would never censor. I would prefer people read Kipling’s work and understand why it should never be repeated, rather than acting like it was never written at all. When you ban a book, you’re not creating silence, you’re constructing an ignorant narrative, a false narrative.

These harsh realities, shown in Maus’ Europe, can also be found closer to home in James Baldwin’s America where his breathtaking prose and cultural critiques construct an astute perspective on America’s racial history. It is no surprise his works have been criticized and banned. By writing authentically — without censoring himself, his identity as a queer man, or his experiences and opinions as a Black man — Baldwin changed my personal understanding of white elitism and race relations. People are once again calling for Baldwin’s novel Go Tell it on the Mountain to be banned from classrooms. Doing so would silence a perspective that marginalized groups, most notably the queer black community, can find representation in. Censoring these stories, whether it be Spiegelman or Baldwin, limits social progress because we are not letting experiences that differ from the status quo be told. Future authors will hesitate to tell their stories if they do not see themselves in the media. We are isolating people, removing their sense of belonging in society, by not giving them the space to tell their narratives.

Maus does what a lot of books try and fail to do; it is honest. And such is my experience with pieces of Kurt Vonnegut’s work as well. He has the haunting ability to create a story so disturbingly real that you feel like someone has peeled back the skin of humanity and dumped its bowels at your door. Perhaps that’s why many of his works have been banned over the years, including Slaughterhouse Five, which lays bare not only the cruelty of war but its absurdity. He creates a humor around war, as if letting the reader in on a secret joke: war is a tragedy too vast for us to not rely on humor to cope. His protagonist is the antithesis of your traditional war hero, showing the reader how war is hell and human nature is neither good nor bad, it just is. This honesty disturbs the reader because it pokes holes into your values. In a way he’s challenging them to look reality in its face, saying, “Here, look at the beauty and the horror of our world. What are you going to do about it?”

Books have always been starting points for difficult discussions. It is in these pages that we teach growth. You cannot hide from history, nor can you erase it. In my opinion, it’s better to address it head on and show the ugly sides of the past than ignore them. You have a better chance of making actual change that way.

Marlena is a senior at Lowell. When she isn't at school she's probably at the lab, watching a movie, or sitting on the sidewalk listening to music (usually Björk).

Susan Anderson • Jul 5, 2022 at 9:39 am

Brilliantly written and incredibly important. Present and rampant Fascism makes resistance mandatory. Read on ~ particularly banned books!