Cuts to the community

Ethnic Studies teacher Carolina Samayoa stood in Room 219, trying not to cry for the third time that day as she dismissed her class. She hadn’t been anticipating the outpouring of dismay and disbelief from her students when she told them she would not be returning to Lowell next year. The mood was bleak as students packed up for their next class.

Samayoa is one of nearly 30 teachers who will most likely not return to Lowell next school year due to an expected $3.6 million budget cut.

As many as 29 Lowell teachers could be without a job next year, according to Dominguez.

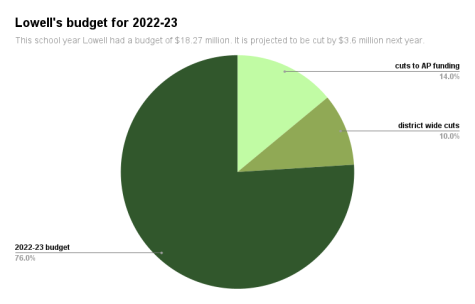

Lowell is slated to lose around 20 percent of its total budget for the 2022-2023 school year due to the San Francisco Unified School District’s (SFUSD) efforts to alleviate the $125 million deficit. All public schools in San Francisco are facing budget cuts — facing the prospect of losing teaching staff and student programs. However, Lowell remains uniquely impacted due to a reliance on AP program funding. In addition to the loss of teachers, there will be a decrease in the number of course offerings at Lowell — over 40 courses will be cut. Community members worry that these budget cuts will have long-term effects on Lowell’s culture, community, and identity.

Budget Breakdown

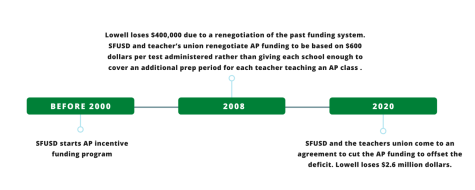

In February of 2022, Lowell was notified by the district that it would be losing around 24 percent of its current funding as a result of two separate district initiatives to decrease overall spending. The first was part of a February contract agreement between the teachers union and SFUSD that paused Advanced Placement (AP) funding for school sites, the intention of which was to increase the salaries for paraprofessionals. Schools that offered AP classes and administered AP tests have previously received major funding through the form of prep periods, which are given to AP teachers to accommodate preparation for their more intensive curriculum. These periods have been funded by payments from the school district of $600 dollars for every AP test a student takes. AP money has given Lowell around $2.6 million dollars per year, according to principal Joe Dominguez. According to Superintendent Vincent Matthews, each school in the district will also receive a 10 percent cut to their total budget to offset the estimated $125 million dollar deficit the district is facing. Together, Lowell will be losing $3.6 million dollars in its budget for the 2022-2023 school year as a result of these two funding cuts, according to Dominguez.

Most high schools in the district will not be as impacted by the financial cuts because they are not as reliant on AP funding as Lowell is. According to Dominguez, 14% of Lowell’s budget comes from AP funding. Around 93 percent of Lowell’s budget is allocated to teachers’ salaries and benefits, which means that AP money is an important part of funding teacher positions. Of Lowell’s $2.6 million received from the district’s AP funding, only around $1.5 million is needed to cover AP teachers’ prep periods. This leaves $1.1 million available in Lowell’s general fund to pay for electives, non-graduation requirement courses, or any additional areas of the school that require funding.

These cuts will have personal impacts on the Lowell community. As many as 29 Lowell teachers could be without a job next year, according to Dominguez. He expects 22 staff members to be consolidated — as the district has stated that no teachers will be fired, simply relocated — and seven staff members to retire. In addition, classes such as language programs (Latin, AP Japanese), Leadership, Visual and Performing Arts classes (Photography, Architecture, Musical Theatre), and electives (Journalism, Yearbook) may be cut, among many others. Community support systems like the African American and Latinx Student Support Liaisons, and the Black Student Union and Latinos Unidos sponsors will also be downsized or eliminated altogether. These cuts to these specific programs have not been finalized. Conversations with department chairs and stakeholders may alter these decisions, and additional funding from the Lowell Parent Teacher Student Association and Lowell Alumni Association may be able to support some programs at risk of getting cut. Dominguez has also asked for $2 million from the district to bring Lowell’s loss of funding closer to other schools’ losses in the district.

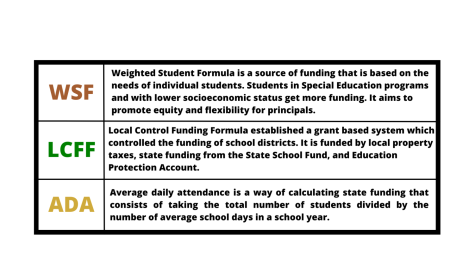

The loss of AP money will put Lowell at the bottom of the rank in terms of funding. “With the cuts to the AP funding, we are now the lowest funded public school in the district,” social sciences teacher Rebecca Johnson said. According to SFUSD’s Weighted Student Formula (WSF) allocations, Lowell’s per pupil funding is currently $6,636 thousand dollars. Next year, without AP funding, it is projected to be $5,781 thousand dollars. The average per pupil funding for a high school in SFUSD is $6,715 dollars.

Since the AP funding source was implemented, there has been controversy over its continuation. In 2008, SFUSD and the teacher’s union renegotiated the past funding system, causing Lowell to lose $400,000. AP Environmental Science teacher Katherine Melvin was on the union negotiating committee for that particular agreement, and claims that the district wanted to cut the AP incentive funding from their contract with the union because they saw it as too much money going to one school. “They show a graph with how much money every school gets, and they show how much money Lowell gets from APs and they say it’s not fair.” Melvin said.

Many feel that this budget cut is indicative of larger issues in the funding of public education. The district allocates money to each specific school based on the WSF, which means that site funding is based on the needs of individual students (see definition table). Executive Director of the Lowell Alumni Association Terence Abad and member of the School Site Council (SSC) — a group of community stakeholders responsible for determining Lowell’s budget — feels that the WSF does not cover all the costs of a high school. “I don’t think any high school in the district could survive strictly on the weighted student formula,” Abad said.

Due to the limited funds from the WSF, Dominguez is facing the hard decisions of choosing which programs to cut and of telling his teaching staff that they will be consolidated, and blames SFUSD for its lack of foresight. “They should have been year-by-year sacrifices, instead of this massive pulling-of-the-rug kind of thing,” he said. Currently, he feels that administrators need to play a more active role early on in the process so that the SSC can have more power in making school site changes. “If they want to make more informed decisions we should have been involved at the very beginning and not whenever we are let in,” Dominguez said.

They should have been year-by-year sacrifices, instead of this massive pulling-of-the-rug kind of thing.

Impact on students

Senior Lavinie Karam-Wijelath is currently enrolled in two classes that are projected to be negatively affected by the budget cuts: Ethnic Studies and Peer Resources. Peer Resources is an elective class that provides a space for students to lead projects that improve the conditions of local communities. For Karam-Wijelath, cutting this means the loss of a class that has given her a sense of community at Lowell. “It’s been a very safe space to talk about everything,” she said. “Knowing that Peer Resources will probably get cut is disheartening because students have so many things they want to change, and Peer Resources is a really good platform for that.” And while Ethnic Studies will remain at Lowell, it’s likely that the current teacher who teaches it, Samayoa, won’t return next year. Karam-Wijelath is sad about her dismissal because of how unique and valuable she feels Samayoa is as a teacher. Having a person of color teaching a history class made Karam-Wijelath feel more represented. Samayoa’s class had always been a safe space for her to learn and form connections with both her peers and teacher.

The entirety of the Peer Resources program, which has a portion dedicated to developing and running programs such as Peer Mentoring and California Scholarship Federation (CSF) Tutoring, is currently projected to be cut. Peer Resources is especially vulnerable because the class has a maximum enrollment of 18 students to allow for more communication among the student leaders. “It would be a heartbreaker for Lowell to not have Peer Mentoring and CSF Tutoring,” Adee Horn, the Peer Resources teacher, said. “I really don’t know what that would look like.” According to Thelma Ramirez, a Peer Mentoring leader enrolled in Peer Resources, the mentoring program played a big role in helping her transition to high school. “As a freshman, I was really shy, but having a mentor helped me a lot,” she said. Ramirez believes that losing the mentoring program would have profound impacts on Lowell students who would no longer be able to receive support.

With the cuts to the AP funding, we are now the lowest funded public school in the district.

Language courses can also be hubs of community for students, but they may vanish under the budget cuts. Senior Amber Lau has taken Latin language classes since her freshman year at Lowell, and has found a relaxed community that allows for more student interaction with classmates and her teacher. “It’s just a place where you can have conversations and give everybody a chance to be themselves,” Lau said. If the Latin language program was cut, Lau believes that future students would miss out on the same close-knit connections that she has developed. “Latin would be a really good space for them to grow as a student and find [their] place in the school,” she said. Other language programs like Japanese have fostered communities that students treasure. After taking Japanese 1, 2, and 3 Honors, junior Naomi Walsh was excited to take AP Japanese and continue to build relationships with her current classmates, before finding out this course is also on the chopping block. “Japanese is one of the only classes where I have known people consistently throughout the entire three years I’ve been here,” Walsh said. “I felt like there was a real community within the Japanese classes.”

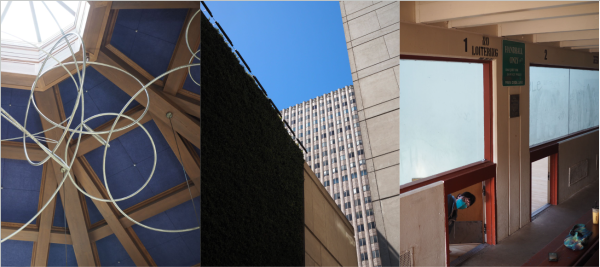

For students like Fillon, VPA classes were a major incentive to apply to Lowell. Fillon transferred into Lowell at the beginning of her sophomore year, excited about its architecture department and numerous VPA classes. However, with Lowell’s architecture and photography teacher retiring, the programs will not be renewed. Lowell’s architecture department opened up opportunities for Fillon to explore her passion for architecture and design, allowing her to apply her classroom knowledge to outside opportunities like competitions. Fillon’s time in Lowell’s architecture program helped her realize her desire to study architecture and design in college, build her portfolio, and even meet her girlfriend. This program has been the jewel of her high school experience. “It’s important to have your interests being expressed by the school, and being given the outlets necessary to further those interests,” Fillon said. She is worried about what the loss of this class and the consolidation of other VPAs will mean for students looking to explore the arts in high school. “It’s honestly very sad because one of the special things about this school and public schools is that they have architecture classes,” Fillon said. “That’s not something that’s provided at very many schools.” As she graduates with the ambitions of studying architecture, she regrets that future students will not be able to have the opportunity she had.

Japanese is one of the only classes where I have known people consistently throughout the entire three years I’ve been here,” Walsh said. “I felt like there was a real community within the Japanese classes.

With several AP courses on the chopping block, some students are concerned about the possibility of a changed academic culture and their futures beyond high school. Junior Cai Marcos believes that Lowell’s range of APs allows students to challenge themselves, which is something she believes her peers strive towards. “AP classes academically give students opportunities to push themselves to a higher level,” she said. Junior Cahn Hung also values the variety of AP classes that Lowell offers because they believe it boosts their GPA and makes their college application stronger. “Obviously Lowell has a huge reputation for AP classes,” they said. To Hung, a stronger college application will boost their chances at acceptance into a prestigious college, which is something they value as a first generation student. “It’s just been my standard ever since I was a child, so boosting my GPA is very important to me,” Hung said. “Which is why the cutting of AP classes scares me.”

The lack of funding may also impact the student incentive to attend Lowell, due to the loss of AP courses. If there is no financial gain from administering AP exams, Melvin does not see a reason for Lowell to offer as many AP classes, which will negatively affect the academic appeal of Lowell. “I think students are going to leave the district because a number of students and a number of families were choosing to come to Lowell because their students had an opportunity to take so many APs,” Melvin said. “I really do think the number of APs and the quality of APs are going to decline.” Some students agree that the changes to a variety of AP classes may change future students’ expectations of Lowell. “I think students will still want to come to Lowell,” Hung said, emphasizing how Lowell next year might not live up to expectations. “They’re taking away things that really make up what Lowell is and what the students really want.”

Teacher Impact

Teachers also face the brunt of these cuts, and many are grappling with changing the way they teach their classes, primarily any AP courses, as workloads shift and grow. With AP teachers teaching 5 blocks instead of 4 — losing an extra prep block — Johnson worries that she and other educators will be unable to dedicate the same amount of time and effort into their students, tarnishing the educational value of their course. “I think all teachers across the board are going to have less time to sit and talk with students,” Johnson said. “I feel like everything’s gonna tighten up. When there’s change, you’re not even gonna realize what’s missing until it’s gone.”

The projected loss of 29 teachers next year prompted the teacher’s union to announce that they would be consolidating departments and teachers based on tenure, or the length of time they’ve been teaching. Now, a number of Lowell teachers are evaluating their next steps. “I will undoubtedly be affected by these [decisions],” said Alex, a first-year teacher at Lowell under a pseudonym. To Alex, the future is bleak; they could either be relocated to another school site or lose their job entirely. Although the daunting process of finding a new job worries Alex, they are more distressed about the loss of the impactful connections that they’ve formed at Lowell. “I’m not going to see my freshmen grow up and graduate,” Alex said. “I was really looking forward to that whole aspect of teaching, especially since I have 140 relationships with my students, and I’m sad I won’t get to see them grow up.” Samayoa echoes this sentiment – she had been hopeful that Lowell’s loss of funding would be reconsidered, but wasn’t surprised to be told that she wouldn’t be returning next year. “I love this district, I love this school, and it will hurt a lot to go,” she said.

Besides the loss of staff, administrators and students worry about how these cuts will impact the racial diversity of Lowell’s teachers. In the last year, Lowell’s moves to diversify its staff had influenced the hiring of more representative teachers. Since these newly hired teachers all do not have tenure, this means that 22 Black and Indigenous people of color (BIPOC) teachers won’t return to Lowell at all next year. Dominguez is frustrated because the Lowell administration’s efforts to increase the diversity of faculty may have been wasted. “We’ve really been making it a focus to recruit and hire a diverse set of teachers,” Dominguez said. “It seems like we’re going to start from zero again and I hate that.” Samayoa is worried about what the loss of teachers of color will mean for minority students. “We’re sending a very implicit message that these students don’t belong here because the adults also don’t belong here anymore,” she said. Samayoa fears these cuts will hurt diversity in the student body because the loss of BIPOC students’ support systems and BIPOC teachers may discourage students of color from applying to Lowell. “We’re harming kids. It’s ugly, and no one deserves it,” Samayoa said.

We’re harming kids. It’s ugly, and no one deserves it,” Samayoa said.

Tenured teachers personally affected by the predicted reduction in staff numbers have banded together to help support those who may be cut. According to Melvin, many Lowell teachers have felt a collective sense of grief about the recent news, and she’s been forced into the “horrible position” of reevaluating her own place at Lowell. She’s even considered giving her job up for her younger, untenured colleagues. “Nobody should have to say, ‘I should really retire now so they can stay.’ No one should ever be in that position,” she said. “But that’s our reality.” A number of tenured and financially stable teachers have voiced considering teaching part-time next year in an effort to keep their colleagues employed. “For every five of us to do that, we can save someone’s job,” Johnson said. Additionally, one outcome of the agreement between the district and teachers union had been the granting of monetary bonuses to teachers; Johnson and her colleagues have started a campaign to donate this amount, dubbed “blood money,” to the LAA or Parent Teacher Student Association (PTSA) in hopes that the funds would be redistributed into the school budget.

As Samayoa stood in the Ethnic Studies classroom, she lamented how students and teachers will bear the brunt of these changes. Gray, plush couches, pushed together in a U-shape echoed the laughter and quiet conversations of her students. The room was dimmed with muted lighting from a string of fairy lights and a few stray lamps. As students filed out of the room, stopping to chat with Samayoa, she felt a surge of pride for her students, and a longing to stay in this community. “The one year that I was here, I feel like I impacted my students,” Samayoa said. “So if that’s all I did at this school, that is good enough for me. I am really proud of my students above anyone else.”

Chloe is a senior, but still doesn’t really feel like one. One thing she’s proud of are her spotify playlists, which include every genre imaginable (yes, even country). Outside of the journ room, she loves taking long drives, writing, and thrifting.

Kelcie is a senior at Lowell who can be found in the journ room working, drinking coffee, and listening to music. Her older brother once mentioned that there are only three guarantees in life: death, taxes, and Kelcie not waking up to her alarms. She also happens to have a paradoxical relationship with chicken… go figure.

Saw is a senior who has been on staff since Spring 2021. Outside of her busy academic life, Saw likes to volunteer at events, explore the city with friends, watch the latest MARVEL movie, and run on Lowell's Cross Country team.

Elise is a senior. This is her third year as an illustrator for the publication. Some of her interests include petting cats, going to museums, and spending unforgiving amounts of money on the evil coffee monopoly that some may know as Peet's.

Harper • Mar 26, 2022 at 9:22 am

Great article! I feel much more informed on the budget issues and impacts to the Lowell community. Thank you for such comprehensive work.