$2.6 million budget cut could lead to loss of 26 teachers

On Feb. 7, 2022, the teachers’ union, the United Educators of San Francisco (UESF), ratified a one-year contract with SFUSD. The agreement will pause Advanced Placement (AP) funding from the district. Before this, the district has paid schools $600 for every AP test taken by a student to fund AP teachers’ prep periods. These cuts will disproportionately affect Lowell due to a systemic reliance on AP money, which brings in around $2.6 million to Lowell each school year. As a result of this, Lowell can expect the loss of between 22 and 26 full-time teachers next school year.

This proposal is part of a larger district-wide budget balancing effort to reduce any non-essential spending. In a February email to SFUSD staff, Superintendent Vincent Matthews wrote that a decrease in enrollment, the hardships of the pandemic, and rising costs have caused a “structural deficit” in the district’s budget of at least $125 million for the 2022-2023 school year.

SFUSD’s original proposal to the teachers’ union was to cut AP funding for school sites permanently. UESF’s counter proposal included a one-year pause on AP prep and teacher sabbaticals, while providing two $2,000 bonuses to all UESF teachers still employed after these budget cuts, as well as a $3,000 stipend for AP teachers. According to the teachers union, the contract will also increase the salaries of paraprofessionals, who are paid less than teachers.

This loss in AP funding is expected to result in teacher layoffs because AP teachers do not teach a full class load of 5 classes; they teach 4 classes and receive one prep period. As a result, Lowell must hire more teachers, thus increasing its budget. According to social studies teacher Monty Worth, the agreement means that each teacher that currently teaches an AP class will need to teach an additional class in place of their prep period. This means that non-AP teachers would no longer be needed to teach those non-AP classes, resulting in their layoffs if they do not have tenure. According to Dominguez, in a worse case scenario, Lowell will lose 22 full-time teachers. However, according to a budget comparison of current school site funding, Lowell could lose as many as 26 full-time teachers. Three Lowell teachers have already received preliminary warnings from the district about being cut. According to Dominguez, in a worse case scenario, Lowell will lose 22 full-time teachers.

AP funding also allows Lowell to offer an array of niche AP classes and much of the elective courses students enjoy, some of which may now be taken away. Of Lowell’s $2.6 million received from the district’s AP funding, only around $1.5 million is needed to cover teacher’s prep periods. This leaves $1.1 million to be used in Lowell’s general fund to pay for electives, non-graduation requirements, or anything else the school needs money for. “Let’s just say the amount of money we recover from AP tests is significant,” former Principal Dacotah Swett said. “We would not be able to have the programs we have here today without that.”

Many teachers at Lowell are not happy with the agreement the teacher’s union reached with the district. Head of Lowell’s math department Karl Hoffman believes that the proposal was sloppily put together and will have disproportionate negative effects on Lowell. He thinks the district is not being mindful enough when cutting costs to offset the deficit. “I think it’s inequitable. I think it’s wrong because it’s taking a sledgehammer to the budget blindly without really taking any care to trim budgets evenly and fairly across schools,” he said. Physics teacher Bryan Cooley mirrors Hoffman’s frustration. “It was a horrible agreement that unnecessarily gutted Lowell’s AP program,” he said.

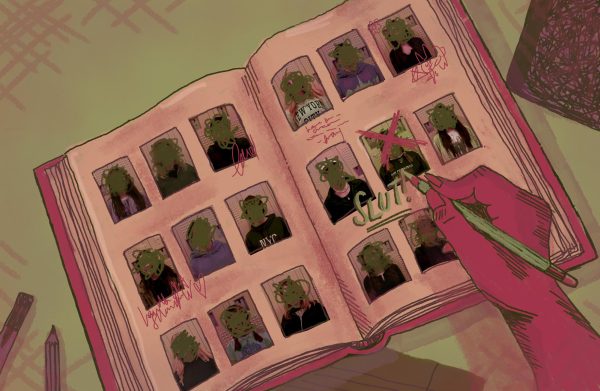

Untenured teachers, like social studies teacher Robert Marshall, are worried about losing their jobs. Marshall, who does not teach any AP classes, does not want to leave the community he has immersed himself in at Lowell. “I just want to keep making connections and see everyone and continue on,” he said. “It would be so sad to leave.” While Marshall has the financial security to sustain himself while looking for a new job, others may not. “A lot of teachers don’t have those kinds of resources and backup — especially teachers of color, which the district is trying to get more of,” he said.

I just want to keep making connections and see everyone and continue on. It would be so sad to leave. — Marshall

School sites like Lowell were already struggling to meet the financial demands of operation prior to this deficit and have long been reliant on alternative funding sources. Executive Director of the Lowell Alumni Association, Terrence Abad — who has spent years as a member of the School Site Council (SSC), a group in charge of outlining Lowell’s budget — feels the primary source of school funding from SFUSD, the Weighted Student Formula (WSF), does not cover all the costs of a high school. The WSF is based on enrollment, but according to Abad, schools across the district need additional funding to cover their entire budgets. Lowell receives less money from Title 1, supplementary grants, and concentration grants than other high schools, which leaves it more reliant on AP money. According to Abad, the money from Lowell’s AP program makes up 14 percent of the school’s budget.

In a school with an operating budget of around $18 million, that money is essential. Around 93 percent of Lowell’s financial allocations are designated to teachers’ salaries and benefits. This means that AP money is an important part of funding teacher positions. Abad believes that a lack of sufficient funding of public education has forced a continued dependence on supplemental funds. All these changes are in addition to the expected 10 percent cuts facing all school sites due to the district’s budget deficit.

This contract has not yet been approved by the San Francisco Board of Education, which will be holding a meeting on this agreement on Feb. 22, 2021.

Teaching positions at Lowell are on the chopping block because less money will be available. Worth and other teachers are unhappy at the prospect of losing jobs or colleagues. “It just seems a real pity to lose very promising people,” he said. “It’s losing teachers that is upsetting us most.”

Layla Wallerstein contributed reporting.